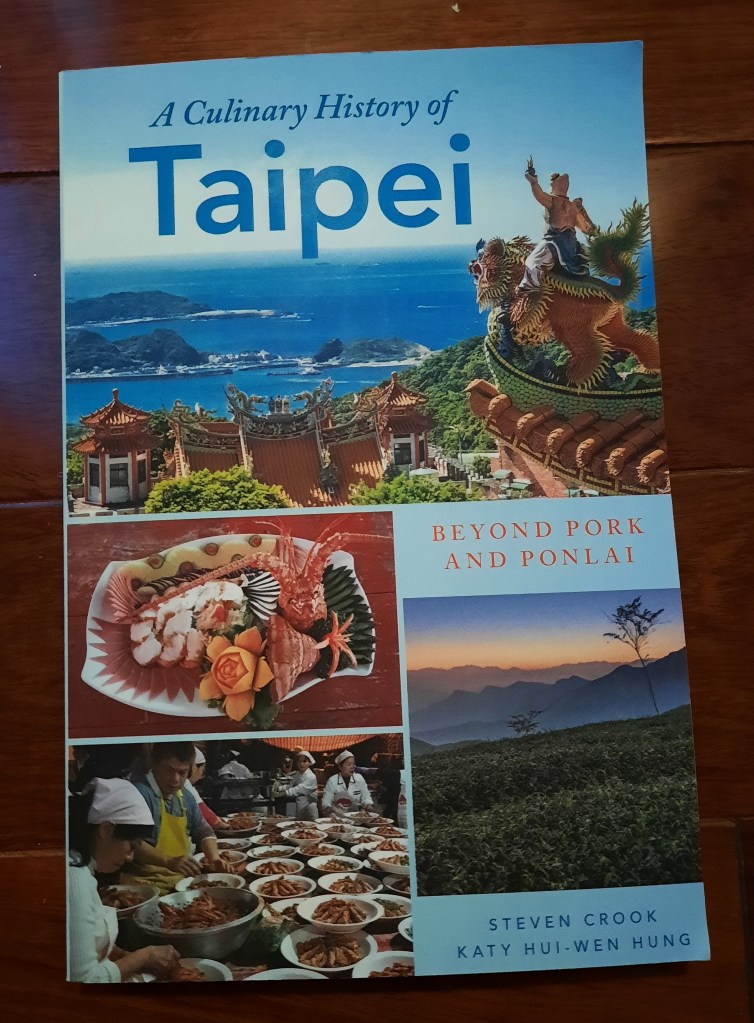

The paperback edition of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, the food book I co-wrote with Katy Hui-wen Hung before the pandemic, was published back in February (I’m told) but not until this week did the authors’ copies reach us here in Taiwan. Hopefully its lower price compared to the hardback will lead to greater sales.

The pleasure of pressing ‘send’

A couple of days ago, Facebook reminded me that it’s been a year since I visited the Southern Branch of the National Palace Museum, which is about an hour by car from where I live. That was one of the first trips I made to update Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide for UK-based Bradt Travel Guides. The first edition of the guidebook came out in 2010, the second in 2014, and the third edition appeared in mid-2019 — so freshening up the contents has been more than due.

I’ve been asked more than once how much travelling I did to write the guidebook in the first place and how much has been needed to revise it since then. The answer is: I don’t know. Early on, I tried to keep track — but I quickly gave up, because many if not most of the excursions I’ve made have had more than one purpose. Sometimes I’ve gone to a place simply because I need to include it in the guidebook; very often, however, I’m going because at the same time I can research a newspaper or magazine article. For instance, the two-day rail trip from Tainan to Taipei via the east of the island I completed this spring generated not just useful material for the guidebook, but also photos and information that resulted in this article and also a good chunk of this article.

This morning I felt a notable sense of relief when I sent off the final map for the fourth edition, having uploaded the last piece of text yesterday. These final few weeks haven’t been unusually stressful, however, because I made sure to get stuck into the task of revising the book as soon as I’d signed the contract. Well before that I’d begun compiling a list of things I should add or delete, as I came across them during other projects (or while travelling for fun). Some of it’s been dreary. Most of it’s been interesting. Hopefully the book’s readers will find it both useful and engrossing.

Memorial dedicated to ex-prisoners of war

The events he describes occurred more than half a century ago, but Jack Edwards has no difficulty recalling them. They were traumatic experiences in a small, densely forested valley just outside the Taipei suburb of Hsintien.

“We had to carry heavy rice steamers, bags of rice and other supplies up from the market to the camp,” he says. “It was six or seven miles each way. We had to carry dead men down on stretchers we made ourselves. And if we moved too slowly, the guards would beat us.”

Edwards, who grew up in Wales but has lived in Hong Kong since 1963, is currently in Taiwan on a tour of prisoner-of-war related sites with fellow British Army veterans John Marshall, Ben Gough, and James Scott, three Scotsmen who were captured by the Japanese Army in Singapore in 1942 and interned in Taiwan until the end of World War Two.

The four Britons returned to the valley yesterday to attend the dedication of a memorial for those held in Kukutsu, as the Japanese called the prisoner-of-war camp. Others present included officials from the British Trade and Cultural Office and Australian Commerce and Industry Office, expatriates, and Taiwanese.

During the ceremony, Edwards spoke of the camaraderie that helped them endure, and the importance of not letting the prisoners’ terrible experiences be forgotten.

Canadian missionary Jack Geddes offered a prayer for the victims. He added that in both European and Chinese cultures, there is a tradition of erecting stones to commemorate historical events, be they tragedies or triumphs.

The Kukatsu Memorial was planned and paid for by members and supporters of the Taiwan POW Camps Memorial Society, a band of expatriate and local history enthusiasts dedicated to researching the island’s prisoner-of-war camps, ensuring that those who spent up to three-and-a-half years in captivity are not forgotten, and educating people throughout the world about this overlooked aspect of Taiwan’s history.

The suffering of the Allied prisoners- of-war forced by their Japanese captors to build a railway through the Thai jungle during World War II is well-known in the Western world. Far fewer, however, are aware that Japan also maintained POW camps in Taiwan and that many of the captured men were forced to labor in inhumane conditions.

“The story of these prisoners-of-war has been largely untold for the past 50 years, so now we’re trying to tell it,” says Michael Hurst, a Taipei-based Canadian who is director of the society.

Taiwan was a Japanese colony from 1895 until the end of World War II. As a secure rear-area abounding in raw mate- rials, such as wood and coal, it served as a staging post for the Japanese military machine during its conquest of Southeast Asia.

Some 2,400 Allied servicemen were held in 11 prison camps around the island. The vast majority (more than 2,000) were British soldiers captured in the early stages of the Pacific War. They were joined by Americans, Dutch, Australians, Canadians and New Zealanders.

Conditions varied from one camp to another, the most notorious being located in the small town of Jinguashi near Keelung. The camp at Kinkaseki, as Jinguashi was called by the Japanese, was centered around a now-defunct copper mine in which Edwards and other Allied servicemen were forced to labor in extremely uncomfortable and dangerous conditions. Of the 1,135 POWs put to work there, more than half died in accidents or as a result of malnutrition and disease.

Through the efforts of Edwards, Hurst and others, corporate and individual donors and the local authorities, a memorial to the prisoners-of-war was dedicated in Jinguashi in 1997.

The Taiwan POW Camps Memorial Society is endeavoring to pinpoint the places where Allied servicemen were held and, Hurst emphasizes, “let the survivors know this, and that they haven’t been forgotten.”

Six have been located so far. The society’s most recent success was in southern Taiwan where, after more than a year of careful research and on-site investigation, the position of the Heito camp near Pingtung was finally determined. With the help of an elderly local man who served as a perimeter guard in the camp (tens of thousands of Taiwanese conscripts served as auxiliaries in the Japanese armed forces during World War Two), the cemetery where dead prisoners were temporarily buried was also identified. This discovery, Hurst says, means a great deal to relatives.

The Heito camp is now a Taiwanese army base, nestled among groves of betel nut trees. Access is difficult, but Hurst is optimistic that permission to erect a memorial plaque or stone in or close to the base will be granted.

Finding the remains, if any exist, of camps such as Heito and Kukutsu is an exercise in historical detective work. Survivors, now in their 70s or 80s, seldom knew where they were being held and were preoccupied with survival. Many, however, have provided the society with notes and sketches based on their memories. Hurst, his wife, Tina, and their friends in the Memorial Society spend much of their free time cross-referencing these with maps from the era, Allied intelligence reports and clues from local residents.

The five camps known to have existed in the Taipei area have proved especially difficult to locate. Redevelopment has changed the landscape radically, and interviewing the local population has yielded few clues because many of Taipei’s current residents come from other parts of the island.

According to Hurst, of the more than 100 former prisoners contacted by the society, only one has been less than eager to relive the memories of those days. Academia Sinica, Taiwan’s most prestigious research institute, has asked the society to share its findings.

The Kukutsu camp had a short but brutal history. When advancing Allied forces cut shipping links between Taiwan and Japan in early 1945, Kinkaseki’s mine was closed and the prisoners moved out. Many, including Edwards and John Marshall, another veteran present at yesterday’s dedication, were sent to the hills above Hsintien.

The two men volunteered to join an advance party responsible for preparing the camp. They reckoned that any other place would be better than the mine, but conditions in “the jungle camp” turned out to be almost as bad.

There was little food and no shelter. Prisoners slaved to clear elephant grass, cut down trees and build huts. They scavenged whatever edible matter they could find. Snakes, snails, worms, grass and leaves served to complement the rations provided by the Japanese.

The prisoners planted sweet potatoes and peanuts but never harvested the crops. The war ended-just in time for many of the men.

“I was in a terrible state by the end of the war. I weighed five-and-a-half stone and could barely walk,” says Marshall.

But not all the POWs’ memories of that time are bad ones. On their trips down the valley to get food, the prisoners would pass a homestead which they called “the half-way house.”

“When the Japanese guards weren’t looking, the Taiwanese family living there would slip up sweet potatoes and other morsels,” Edwards recalls. In 1946, when he returned to the island to assist with war crimes investigations, he visited the family and thanked them for their kindness.

Tidying up recently, I rediscovered the original print version of this 1,194-word feature I wrote for Taiwan News back in 2000 about a POW memorial in Xindian, New Taipei (then Taipei County’s Hsintien City). Jack Edwards died in 2006. As of early 2025, Micheal Hurst MBE remains director of Taiwan POW Camps Memorial Society.

A Lonely Crusader? Chen Lih-ming’s Campaign against Religion

Outsiders often express admiration for Taiwan’s lively and diverse religious landscape. The authors of the most recent edition of Lonely Planet’s travel guide to the country are among those who paint a positive picture, enthusing: “Over the centuries the people have blended their way into a unique and tolerant religious culture… Taiwan is a country with many temples and many gods.”

Not every Taiwanese sees religion in a favorable light, however. Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟), characterizes the country’s religiosity as “ridiculous.”

Chen isn’t concerned with how religious practices impact people’s physical health. His responses to this reporter’s questions make no mention of the air and noise pollution that temples often generate.

Nor does he talk about a widely-reported study conducted by National Taiwan University’s (NTU) College of Public Health almost 20 years ago. NTU researchers concluded that babies exposed to year-round incense-burning at home are 44 percent more likely to experience delayed gross motor development than children whose parents don’t burn incense.

“All religions are equally poisonous for society and for individual life. I think people come to religion for two reasons. One is the fear of death. Humans invent religions to ease that fear. Another is their bafflement as to the origin and structure of the universe,” says Chen, who used to teach university-level courses in thanatology, the interdisciplinary study of death.

After giving his students a grounding in modern astrophysics and how it explains the universe, Chen says, he told them that no historian can present evidence that Jesus returned to life after his crucifixion or that Buddha attained nirvana. “Some students challenged me, but after arguing they’d at least think I have reasons for my opinions,” he recalls.

Chen, who says he had a secular upbringing, is convinced there’s no life after death. Instead he believes “the only thing you have is your imperfect, uncontrollable, and limited life. Therefore you must cherish it. Buddhist teachings destroy your life, which is your only treasure.”

The retired lecturer — who’s contributed opinion pieces on politics to the Liberty Times under the pseudonym Chen Che (陳哲) — says that, while he was studying philosophy in Germany in the 1980s and 1990s, the decline of Christianity in Europe was obvious. But when he moved back, he was surprised to notice that Taiwan’s religious groups seemed to be prospering like never before.

Chen points out that, with the exception of continuing support for the death penalty, Taiwanese society seldom defies international trends. He goes on to suggest a few reasons why, well into the 21st century, religious identification and participation don’t seem to be declining here like they are throughout the West, in Japan, and in South Korea.

“Taiwanese people are by nature friendly and tolerant. Most of them would say that religions teach people to do the right thing. Secondly, Confucian influence might provide the soil in which faiths can develop,” he says.

What’s more, he argues, almost anyone can establish a Buddhist, Taoist, or folk place of worship. Unlike in Christian societies, where clergy are expected to undergo years of training, in Taiwan there’s no tradition of attending a religious academy.

“Some people see founding temples as a way to make money. They might consider opening a grocery store or a restaurant, but if they think a temple could bring in more money, they’ll start one,” he says, adding that some of “religious entrepreneurs” are dishonest from day one.

In Chen’s opinion, only when people behave correctly out of a sense of morality are their actions truly moral. “Doing good things because you’re promised paradise in the afterlife isn’t morality,” he says, labeling such behavior as heteronomy (nonmoral actions influenced by a force outside the individual; the opposite of autonomy).

Because the Bible is littered with heteronomous ideas, and asserts that only Christians have a chance of going to heaven, Christians see themselves as “God’s pets, with special privileges,” says Chen. “People expect fair treatment from God, but God cares more about membership than deeds. This is immoral.”

When heaven is his goal, “morality is only a tool or means,” says Chen, insisting that “many religious people use their privileges to do evil things.”

He adds that while Buddhism, Taoism, and popular (folk) religion agree that shan you shan bao (善有善報, “good deeds have good rewards” or “what goes around comes around”), “traditional Taiwanese religions lack clear heteronomous texts.” Nonetheless, their followers also worship deities because they believe they’ll gain some benefit. In his opinion, “Buddhists and Taoists are no less hypocritical” than Christians — and this is why he refuses to say that one faith is better or worse than another.

Chinese-language editions of books by three of “The Four Horsemen of New Atheism” — Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, and Christopher Hitchens — have sold fairly well, but the writings of Sam Harris have yet to be translated for Taiwanese readers. And, so far, no local thinker has come up with a book-length critique of religion, Chen says.

Some ex-Buddhists and ex-Christians in Taiwan have published criticisms of those religions based on their own experiences, but in Chen’s opinion few of them know all of the weak points of those faiths, and they’re unable to tackle issues across the religious spectrum.

Chen is working on a book about thanatology, in which he’ll cover some aspects of religion. “I don’t know if there’s anyone in Taiwan who’s truly qualified to write a comprehensive anti-religion book and who plans to do so,” he says.

It’s going to be a while, it seems, before Taiwan has a Dawkins- or Hitchens-type public figure.

Anti-religion groups are active in many places. In English-speaking countries, humanist associations have grown in prominence. In Japan, the National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales assists victims of cults. The Federation of Indian Rationalist Associations coordinates the efforts of 83 organizations in the world’s most populous country.

No comparable body has yet emerged in Taiwan. Chen’s Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance is currently a Facebook group with around 1,400 members. He’s not aware of any legal reasons why he couldn’t register an NGO with explicit anti-religion goals, he says. But neither does he expect any politicians to help his campaign.

This was written as the first half of an intended two-part article, but the Taipei Times opted to run the second part only, which can be read here. I took the photo at Qingliangshan Huguo Miaochong Temple in Kaohsiung’s Liugui District.

Chiayi’s Claim to Culinary Fame is a Humble Turkey Dish

If there’s one thing nearly every town in Taiwan seems to have, it’s a delicacy it claims as its own. In some cases, the association seems contrived. But when it comes to Chiayi, its claim to fame is unquestionably well-earned. Chiayi Turkey Rice (嘉義火雞肉飯, jiayi huoji roufan) – the city’s iconic dish – lives up to its name and reputation. Located three hours south of Taipei by car, Chiayi has made this humble yet flavorful dish a cornerstone of its culinary identity.

For many local diners, the dish ticks all the major boxes. When prepared well, it satisfies without being overly oily, salty, or sweet. For curious first-time customers and long-time foodies alike, Chiayi – standing at the center of the island’s turkey-farming region – boasts an exceptional concentration of eateries serving steamed white rice topped with finely shredded turkey meat.

Chiayi Turkey Rice’s legacy extends far beyond its hometown, tracing its roots to a fascinating history of turkeys in Taiwan. The dish’s rise to prominence is closely tied to the postwar boom in turkey farming, a phenomenon that transformed this once-rare poultry into a staple of Taiwanese cuisine.

One notable origin story of Taiwan’s turkey population dates back to the Dutch East India Company’s occupation of Tainan (1624–1662), during which the first turkey is said to have been consumed on the island. Another retelling mentions the interpretation of “long-necked birds” in Qing-era documents as evidence that turkeys were being raised on southern Taiwan in the late 18th century.

What’s known for sure, however, is that by 1921, the Japanese colonial authorities on Taiwan were encouraging rural households to raise turkeys as a sideline. The birds had a diverse economic value, from producing meat and eggs to stuffing bedding and upholstery, made possible by instructing farmers to process the feathers for other uses.

Domestic production of turkeys multiplied after World War II, as the island’s human population grew and meat became more of a dietary staple, with hefty turkeys even finding their way to temples as food offerings.

It seems that Thanksgiving purchases by American military personnel stationed on the island between the early 1950s and the late 1970s, combined with exports to Hong Kong, were enough to push up prices ahead of each holiday season. According to a 2015 paper by Chen Yuan-peng, a professor of history at National Dong Hwa University, Taiwanese consumers of that era weren’t always aware they were eating turkey, as the meat was often processed into nuggets, steaks, or hams…

To read the rest of this article, pick up the January 2025 issue of Taiwan Business Topics, or click here.

Rising to the Battery Challenge

After a long struggle to tackle e-waste, Taiwan, particularly through the Ministry of Environment, has managed to get both manufacturers and the general public to follow proper recycling practices, understand the harm caused by improper disposal of electronic devices, and comply with product take-back and recycling regulations.

According to the Executive Yuan, last year’s recycling rate for discarded electronics and household appliances was around 85.9%, possibly the highest in the world. The International Telecommunication Union reported that Europe, the leading region in e-waste recycling, had an average documented recycling rate of 42.8%, while the global average only reached 22.3%. A combination of public awareness, corporate responsibility, and government regulations in Taiwan is paving the way for even greater progress.

The system in place does a good job when it comes to recycling devices, such as laptops and smartphones. However, like most of the industrialized world, Taiwan is bracing for a vast increase in the number of batteries requiring disposal as electric vehicles (EVs) replace those that burn gasoline or diesel. The annual volume of waste batteries in Taiwan is expected to grow from around 792 metric tons in 2023 to 2,020 metric tons in 2025, and as much as 48,077 metric tons in 2035.

Most EVs are powered by lithium-ion cells due to their high energy density and efficiency. Around 85% of global lithium production goes into batteries, as does 70% of the world’s cobalt, which provides stability to the battery, and more than 10% of its nickel. There’s enough extractable lithium for every household on the planet to own an EV, yet there are concerns about mining and refining capacity.

Some analysts have warned of a production bottleneck as early as next year. The bottleneck is not the availability of lithium itself, but the infrastructure needed to extract and refine it at a pace that can keep up with rising global demand. Even if they are wrong, two compelling arguments support retrieving and reusing lithium from end-of-life batteries.

The first is strategic: China dominates the global lithium refining industry…

To read the rest of this article, pick up the September issue of Taiwan Business Topics, or click here.

The Treasure Tree of Old Taiwan

Taiwan is a realm of fantastic biodiversity. There are birds, frogs, snails, and freshwater fish found nowhere else on Earth. But for many of the pioneers venturing into the interior in the 18th and 19th centuries, these creatures were of no interest. They were searching for a particular tree species: Cinnamomum camphora, commonly known as the camphor laurel.

Camphor trees are found in various parts of East Asia, and the waxy aromatic solid that can be produced by steaming camphor-wood chips has long been popular as an ingredient in perfumes, an insect repellent, and a traditional medicine. Even now, many popular balms and decongestants are between 3 and 10% camphor. It was the essential ingredient in smokeless gunpowder, and is often burned during Hindu religious ceremonies.

For Chinese migrants spreading beyond Taiwan’s western lowlands, unexploited stands of Cinnamomum camphora were like seams of gold. For the various regimes that governed Taiwan between the late 17th and mid-20th centuries, however, the trade was too lucrative to ignore. In the 18th century, unauthorized felling warranted the death penalty. Soon after Japan took control of Taiwan in 1895, the Japanese colonial authorities established a state monopoly over camphor wood and oil.

Demand for camphor surged in the late 19th century, thanks in part to the invention of celluloid photographic film. At one point, the island was responsible for more than half of the world’s annual camphor production.

By 1911, however, another scientific breakthrough had undermined the state monopoly. Mass production of synthetic camphor was bad news for the colonial government’s finances, but ensured the survival of Taiwan’s remaining camphor groves.

Visitors to Taiwan who are curious to see Cinnamomum camphora trees and relics of the camphor industry needn’t go far out of their way. Even after the species had lost much of its economic value, the authorities continued to plant camphor trees to provide shade and stabilize slopes. Drought-tolerant when mature, they can thrive even during the long dry spells that are common during Taiwan’s winters.

To celebrate Kōki 2600 (the 2,600th year on Japan’s national calendar) in 1940, hundreds of families living in Nantou County’s Jiji Township were ordered to plant and nurture camphor saplings along what’s now designated Road 152.

Each tree was assigned to a particular household, and if the police noticed that a tree hadn’t been watered, they visited the head of the negligent household to remind, admonish, and sometimes punish. The policy was strict but successful. Nowadays, the 4.5-km-long “green tunnel” draws countless photographers and cyclists.

Throughout Taiwan, certain trees have been sanctified because of their age or size. Often, they’re associated with shrines dedicated to Tudi Gong, the local earth god. An especially impressive “sacred tree” stands at the heart of a tiny village half an hour’s drive from Jiji Green Tunnel.

The 26-m-tall Yongxing Giant Camphor, near Yongxing Elementary School in Shuili Township, is thought to be more than 300 years old. It’s accompanied by two of its descendants—sturdy trees in their own right—and all three are wrapped with cummerbund-like red sashes to symbolize their divinity.

If family or business commitments are keeping you close to Taipei, one of the best places to get in touch with Taiwan’s camphor heritage is Maokong in the southern part of the capital. While they don’t feature nearly so many camphor trees as Jiji Green Tunnel, Maokong’s Zhangshu (“Camphor Tree”) and Zhanghu (“Camphor Lake”) trails provide access to a highly appealing corner of the foothills.

As well as tremendous views, hikers can see wildflowers, a traditional piggery, and some of the farms that have made Maokong famous for its baozhong and other teas. The Zhangshu Path is a mere 1.2km in length, while the Zhanghu Path is twice as long. When combined with a ride in the cable car that connects Maokong to Taipei Zoo Metro Station, and a leisurely meal at a local teahouse, it’s very easy to spend an entire day here.

If you’re more interested in the process by which camphor trees were turned into valuable commoditiesoil, there’s no need to leave central Taipei.

National Taiwan Museum’s Nanmen Park campus occupies part of what was once the largest camphor-refining facility in the world. Within, an intriguing exhibition filled with models and multilingual information panels describes both the crude extraction method used in the early days by camphor teams in the foothills, and the scientific techniques adopted in the 20th century.

The former was labor intensive; men worked without machinery to reduce each tree to a pile of chips. The latter required far less human sweat, and yielded camphor oil of up to 99.8% purity.

Chinese-speaking travelers who make it to central Taiwan can learn about, and try their hand at, traditional camphor processing. In Taichung City’s Dongshi District, the Camphor Story Experience Hall displays antique equipment and offers various DIY experiences.

The hall belongs to a family firm that’s been making and selling camphor soaps and mosquito repellents since the industry’s heyday. Now that the public is embracing natural and artisanal products, it’s finding a new niche, and helping to bring the aroma of Taiwan’s treasure tree back to local households.

This article originally appeared in EVA Air’s inflight magazine in 2019. I took the photo in Nagasaki, Japan, last month.

Writing for Cathay Pacific

The publishing arm of Hong Kong airline Cathay Pacific recently asked me to put together two Taipei-focused articles for their online guide. One, called “Getting to know Taipei” introduces well-known tourist attractions such as the National Palace Museum and the Maokong Gondola, plus a few personal favorites, among them the sublime Dalongdong Baoan Temple (where I took the photo here) and Wulai’s Neidong Forest Recreation Area. The other, titled “The best things to do while on a work trip in Taipei,” takes a slightly different approach while also making accommodation, dining, and sightseeing suggestions. Both are accompanied by sumptuous images — none of which are mine, I should clarify — and links so readers can find out more.

Recent Taipei Times environment columns

I kicked off this year’s environment coverage with a piece on carbon-footprint labeling, which is something just a handful of Taiwanese companies have embraced, in part because it’s troublesome and involves some expense. Because the Lunar New Year was fast approaching, I then explored options for consumers who’d rather donate unwanted items or pass them along to people likely to use them, instead of consigning them to the trash incinerator.

Early in the Year of the Dragon, I interviewed an inspiring Taipei-based scholar for some local perspectives on the four-day work week movement, which last year unsuccessfully petitioned the government to consider shortening the working week. In March, I returned to the complex and often frustration reality of renewable energy in Taiwan, and explained why the country isn’t likely to make rapid progress in reducing the amount of coal it burns.

For the three articles that followed, I focused on what’s happening in the countryside. The problem of free-roaming dogs (which kill birds, muntjacs, and endangered leopard cats) has, if anything, got worse in the last few years. A two-parter on the ongoing loss of farmland and green spaces questioned the government’s approach to unlicensed factories, but at least I could tell an optimistic story from one corner of Yilan County, where a rice farmer asked for and was given public support in her effort to hold back the tide of development.

The Year in Review, sort of

I’m still in Taiwan, still writing, still editing, and still beguiled by strange old buildings like this one I spotted for sale in Kaohsiung’s Luzhu District a few months back.

In the second half of 2023, I edited a soon-to-be published 73,874-word geopolitical analysis of the multifaceted threat that China poses to the United States, as well as dozens of op-ed columns, local government puff pieces, and brochures (both physical and digital) for clients in the cultural sector. I’ve kept up my writing for Taipei Times; among the most interesting or personally satisfying pieces I wrote for them were three which examined the handling and recycling of e-waste such as batteries and LCD panels (here, here, and here), and a look at the degrowth movement and why it struggles to gain traction in Taiwan.

At the end of October, Taiwan Business Topics published my answer to the question “If China blockaded Taiwan, would the island starve?” The TLDR version is: Not for six months or so, but after that things could get difficult.

I don’t go out of my way for travel stories these days, but a three-day junket to Taitung in October resulted in a pair of articles that, I think, came out well. The quinquennial Paiwan Malijeveq Festival was truly memorable, and I enjoyed every second of the morning we spent with an indigenous wild-greens specialist.

What do I expect 2024 to bring? More of the same, mostly. A county government I’ ve not previously worked with has invited me to edit their biannual English-language magazine. One of the reasons for me accepting the job was that the young people I’ll be working with seem sensible and highly motivated. And I’ll be keeping my fingers crossed that the worrying state of the world doesn’t upset a whole load of apple carts.